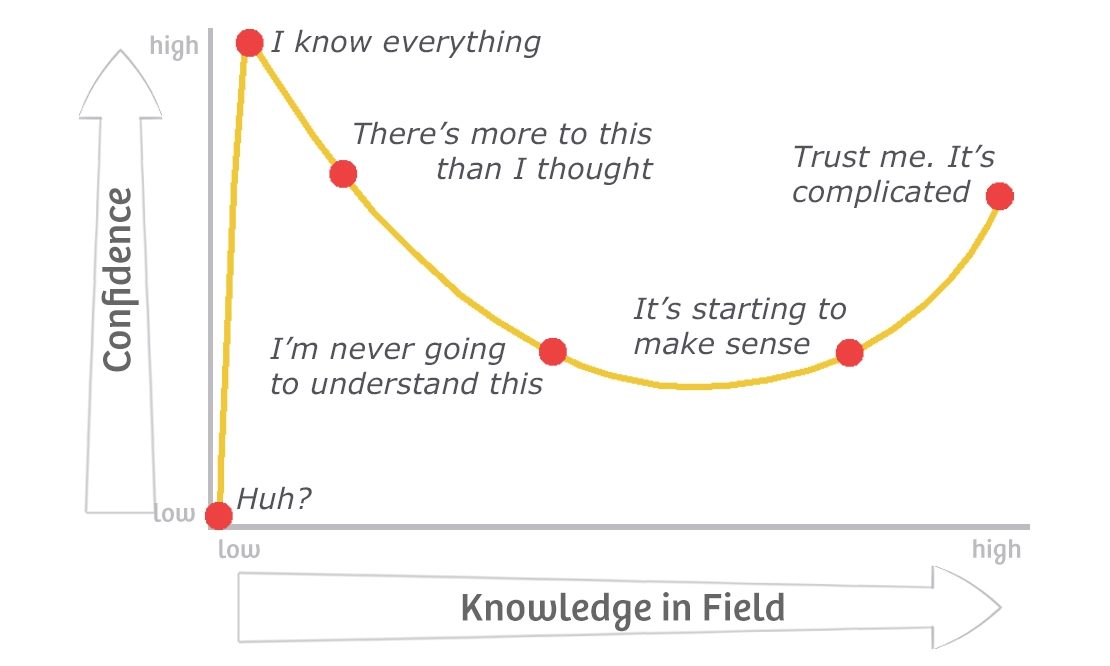

If you gain some knowledge on a subject you knew nothing about, you tend to over-estimate your understanding. This reaction of ‘Now I know everything’ is a well-known phenomenon and it’s called the Dunning-Kruger effect. You feel like an expert!

My lecture series on China in the 21st century this spring coincided with the broadcasting of an immensely popular documentary series about China by Ruben Terlou. His Travelling through the heart of China was broadcast every Sunday evening on national Dutch television. Every Monday afternoon, I had a class of 55 people who were convinced they knew everything there was to know about China, or at least about the theme of last night’s program. How to deal with that in a positive and inspiring way?

Illusion of knowledge

This ‘Now I know everything’ reaction is called the Dunning-Kruger effect. If you gain some knowledge, you tend to over-estimate your understanding. You feel like an expert! But alas, you assess your cognitive capability as much greater that it is. In other words, you suffer from the ‘illusion of knowledge’. It will take some time to realize that there is more to the subject than you initially thought.

The reverse is also true: if you have gained a massive amount of knowledge on an issue, you tend to see the complexity of it: ‘I will never understand.’ Hopefully, at some point, it will all start to make sense and that might be when you have really become an expert. But if you suffer from the ‘imposter syndrome’ you will always feel you’re not good enough as a teacher or trainer.

The more you know…

Western and Eastern philosophers have both written about this: ‘The more you know, the more you know you don’t know’ is a statement that’s attributed to the Greek philosopher Aristotle. And Confucius explains in his Analects (2:17): ‘To know what you know and to know what you don’t know, that is true knowledge.’ After peeling away many layers, even more layers and deeper knowledge will be revealed. In his play As You Like It, the playwright Shakespeare uses a very compelling description: ‘The fool doth think he is wise, but the wise man knows himself to be a fool.’

The Truth?

In order to understand my own student’s observations, I decided to watch every episode on Sunday before class. Terlou has a very charming and empathic style and – with his command of the Chinese language – he knows how to disarm his interviewees. He has that special ability to make people open up and speak their mind. But not everything he says is applicable to all situations all over China.

Obviously, there are vast differences between the cities and the countryside, between different generations, between the north and the south, etc. So it’s impossible to present one all-embracing ‘Truth’ about China. Terlou is fully aware of the complexities of this vast country, of course, but this is what stuck in people’s minds, it’s their perception.

Simplify

So this is the effect of what we do when we – trainers, teachers, journalists – simplify. We leave out complex details in order to provide our audience with some basic understanding. For deeper knowledge, those details and contextual information are of vital importance.

In a series of lectures, I can provide nuance and evade black & white simplicity. It also helps to interact with the audience, raise questions and make them contemplate. But during a workshop, when I only have a couple of hours, I present easy-to-digest images to make my point. That leads to very happy participants: they leave thinking they now know all about the subject. But the lesson of the Dunning-Kruger effect for me is that pleasing my audience is not the best way.

Maybe next time, I’ll finish my workshop like this: ‘I have worked hard to present this in a simple way, to give you some basic understanding. But if you want to gain more in-depth knowledge, please come to the next session.’

Great article Ardi!

Really enjoyed this, Ardi. Now I know a bit more!

I agree that there is massive diversity within China. In any case, knowing China (or anywhere else) is never enough in itself. If the objective is to interact or do business with or live in China, you also need the cultural intelligence that comes from three things: 1. Know yourself – cultural self-awareness is crucial as well as knowing how you are seen by the Chinese (target culture) . 2. Know them – this is where Ardi’s piece comes fully into play. The need for curiosity is vital, here. 3. Be yourself – don’t try to be Chinese or copy behaviours. Be sensitive to etiquette issues but remember only 10% of the iceberg is above the surface.

I hope this makes sense.